Our Patients:

Delaney Batchelder

To mother Angela Ford, the giggles are sounds of miracles. Eighteen weeks before birth, Delaney was diagnosed with a chest mass that would have prevented lung growth during her remaining weeks of gestation. Angela was referred to the St. Louis Fetal Care Institute at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Hospital and Delaney became the second baby in the U.S. to undergo a new fetal procedure to shrink the mass.

“Being number two in the country to have this surgery is amazing,” Angela says as her eyes brim with tears. “If she had come along one year earlier, I wouldn’t have had the ending that I did.”

Angela Ford had been looking forward to seeing her baby on ultrasound for weeks when she visited SSM Health St. Joseph Hospital – Lake Saint Louis on June 21, 2012.

“I could tell immediately that something was off,” Angela says. “The technologist left the room and came back with someone else. They said they had found something they did not understand––it looked like the heart was on the wrong side of the chest. They were sending me to see a specialist. I was really scared.”

“I asked them to come in to the St. Louis Fetal Care Institute for a more in-depth ultrasound, which is when we saw the large mass,” recalls maternal-fetal specialist Mike Vlastos, M.D., FACOG, director of the institute and assistant professor at Saint Louis University School of Medicine.

Angela learned that day her baby would be a little girl she would name Delaney. Also she learned that Delaney’s only chance at life might be a fetal intervention performed only once before in the United States at only one medical center.

The St. Louis Fetal Care Institute was founded in 2009, combining the maternal-fetal specialists at SSM Health St. Mary’s Hospital – St. Louis, the pediatric specialties at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon and Saint Louis University School of Medicine. The institute was one of the few in the world offering surgical and minimally-invasive interventions for diseases arising during gestation.

About two dozen centers in North America and a handful in Europe are pioneering these procedures. Awareness of these problems has risen since about 1969 when diagnostic ultrasound came into routine use during pregnancy. Until recently, high-risk conditions could only be monitored, not treated, prenatally.

The mass in Delaney’s chest was diagnosed as a bronchopulmonary sequestration (BPS), errant lung tissue forming without connection to the airways and drawing its blood from the body’s largest artery.

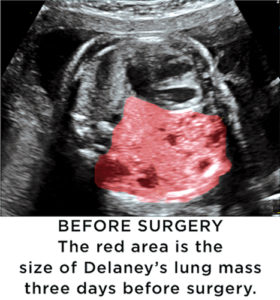

“These masses have a great blood supply, allowing for their own rapid growth and thus compromising normal lung tissue growth,” Vlastos says. “The mass doesn’t allow the lung on one side ofthe chest to grow very well. It also pushes the heart to the other side of the chest, where it compresses the other lung.

“Prior to the advent of ultrasound, these masses were not detected until after birth — the babies would be born and look fine but have an inability to get enough oxygen in the blood. They would die within minutes to hours of birth.”

“These masses show up in one in 2,000 to 20,000 babies,” Vlastos says.

“In most cases a BPS stops growing or even regresses during the third trimester. Only about 10 percent of those get to the ‘bad actor’ category. Even among the ‘bad actors,’ very few reach the extent that intervention during pregnancy is needed.”

Angela underwent weekly ultrasounds at the Fetal Care Institute to see how Delaney’s mass would act. Angela learned to read the ultrasound images shown on the video screen. “Before they would say a word to me I would know,” she says.

Week after week she saw the mass filling more of Delaney’s chest. “There was a really good possibility that if we didn’t do something my daughter wasn’t going to have enough lungs to breathe.”

“In Delaney’s case, things lined up in the ‘bad actor’ category,” Vlastos says. “At around 25 weeks’ gestation we were seeing only continued rapid growth of this mass.”

BPS had been recognized for decades without a possibility for intervention before birth. In 2006, as global interest in fetal intervention increased, a treatment was pioneered at Leiden University Medical Center in The Netherlands. It was called “single-needle laser treatment.”

“It is very elegant,” Vlastos says. “A needle is placed through Mom’s tummy, through the uterus and into the baby’s chest. A very fine laser fiber is inserted through that needle. Then the energy of the laser ablates the blood flow to the mass. When the mass no longer has a blood supply, it begins to shrink.”

This procedure, while technically challenging, is nearly non-invasive and poses fewer risks than an open fetal surgery. The procedure was explained to Angela and she was told that it had only been performed once previously in the U.S. — by her maternal-fetal specialist, Dr. Vlastos.

“It was astounding,” she says. Vlastos discussed Delaney’s diagnosis with the Leiden doctors and a Canadian doctor who had performed the procedure. “The fetal intervention world is very small,” he says. “Most of us know each other.”

Angela was taken into the operating room on Aug. 3, 2012, at 25 weeks and four days of gestation. “It was terrifying and at the same time the only hope I had,” she says.

The operating room team positioned the fetus to provide the best approach. A needle 1/8 of an inch in diameter began its complex journey through Mom’s tummy and Delaney’s chest.

“The baby is given an injection to assure it is unconscious, just as if you needed to go to sleep to have an operation,” Vlastos says. “The fetus can move. If you push on the baby with the tip of the needle, the baby can spin or rotate. Guided by ultrasound, the blood vessel to the mass is found. The needle tip is placed into the baby’s chest and then into the mass.

“Next, the last fiber is placed down the needle and next to the blood vessel. The goal is to stop the blood flow that is feeding the mass, but you must avoid causing any harm to the baby’s aorta, the largest blood vessel that feeds the whole baby.”

The laser fiber is as thick as a human hair but carries sufficient energy to stop blood flow to the BPS’ feeding blood vessel and immediately seal the wound.

“It is a unique moment when you step on the pedal that allows the energy to go through the laser fiber,” Vlastos says. “You’re watching the screen to make sure the heart rate stays good and the aorta is not damaged.”

“I was under anesthesia for around six hours,” Angela says. “I was put to sleep thinking, ‘As soon as I wake up I will know.’ The next thing I remember is waking up in recovery – they said she was okay.”

“We now have performed four of these procedures and have experience with the post-operative, weekly ultrasound evaluations,” Vlastos says. “Usually in the first and second week, we don’t see much change. By the third week, the mass starts to shrink. From that point forward, it becomes smaller and smaller. The heart moves back into the middle of the chest and the lungs on each side expand in a normal fashion.”

The first three babies who underwent this procedure at the Fetal Care Institute have been born with healthy lungs. The fourth is due this spring.

If an open surgery had been needed to remove the mass, Angela would have required a Caesarean-section delivery. Because the procedure used only a needle, Angela was able to carry Delaney to term and have a normal vaginal delivery. On Nov. 7, 2012, as the delivery team at SSM St. Mary’s watched anxiously, Delaney entered the world. She cried. And suddenly she was pink.

“They put that little monitor sticker on her and did their testing,” Angela says. “She was at 100-percent blood oxygen saturation. It was the best thing in the entire world!”

“We estimate that Delaney had 98 percent of normal lung volume,” Vlastos says. “She will have a typical life without any compromises. Best story possible!”

The tiny remnant of the mass that remained in Delaney’s chest was removed when she was 7 months old.

“As her mom, I naturally think she is a little bit more advanced than the usual 16-month-old,” Angela says with a giggle. “Every single day I marvel at her. She loves to be read to. My grandma babysits when I am at work. Delaney wants to read the same book ten times a day! She wants to know the whole cast of characters. She reads and snuggles. It is awesome all day.”

The generous support of many will take the St. Louis Fetal Care Institute to its fifth anniversary this summer.

Over the last four-and-a-half years, the institute has seen 754 patients from 12 states. Urologic and cardiac issues have been the leading diagnoses, followed by twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome and other issues associated with multiple pregnancies. Brain malformations, genetic syndromes, myelomeningocele (spina bifida), masses/tumors and cleft lip/palate also are seen often.

Referrals have doubled since the first year. Most patients do not require a procedure but receive pre-delivery planning and care from any needed subspecialists at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon and SSM Health St. Mary’s.

“The coordination of care is the mantra of the Fetal Care Institute,” Vlastos says. “All of these people come together to help one kid – it is fantastic.”

“Many physicians will see two or three of these types of conditions in their careers, where we see them on a daily basis and can support the families through a difficult time in their lives,” says Katie Francis, R.N., program coordinator of the institute.

The institute’s facilities at SSM Health Cardinal Glennon were built with private donations to the SSM Health Cardinal Glennon Children’s Foundation, including the Saigh Foundation who has provided generous support to further the development of the institute.

“Some of our interventions are expensive and some families come with no means whatsoever,” Vlastos says. “Some of our procedures are considered experimental and are not covered by insurance. Philanthropy has been paramount in helping these kids.”

“SSM Health Cardinal Glennon, SSM Health St. Mary’s and Saint Louis University School of Medicine have continued to advocate for these babies and have donated services. Working in an organization with this philosophy allows us to push the envelope, to develop techniques for helping the babes in the womb and then improving the lives of the newborns and their families.”